We continue the “League of Pros" - stories of people who work in our football and make it better.

Evgeny Ovsyannikov has been with Arsenal all his life. At the age of 11, he first attended an Arsenal match in the Second League of the USSR, at 15 he wrote his first article about the team, and at 16 he became an announcer at home matches. Having worked with the club for many years as a journalist and announcer, having survived their fall into the amateurs, Ovsyannikov became the club's press officer and, together with Arsenal, went from the amateur Collectives of Physical Culture to the Europa League.

"On the first trip I forgot my passport – they put me in the hotel under the name of a football player”

"The first time I came to football in Tula was in May 1979. Then I played for TOZ - the team of the Tula Arms Factory, the predecessor of Arsenal - and for some reason it seemed to me that our team, if not the strongest, was then very good and should beat everyone. The fans, the people at the time, laughed at me and shattered my illusions - TOZ lost the match. In the late 1970s, Tula played in the Second League and were weak, but football was sunk into my soul, and in 1980 I signed up for the section team called "Veterok", representing the machine-building plant.

I really wanted to be like the midfielder Nizam Nartadzhiev from Pakhtakor. He had started the season very brightly with five or six goals. As a result, there was a short story with football: the conditions were not very good, they played on the harem field, and the coach drank, allowed rudeness – it seemed to me superfluous, wrong. I trained for about a year.

When I was 15, I wrote my first article about football. My older brother Nikolai had a good relationship with sports – he played table tennis, worked out on exercise machines, and watched football and hockey on TV – and knew people on the regional sports committee. There I met journalists and learned to write from them. My first article "Major Ending" was published in the oldest regional newspaper "Kommunar" – it no longer exists. I wrote about how TOZ had had a good end to the first half-season in the summer of 1983. Then they had a respected coach in Ivan Vasilyevich Zolotukhin, whom the fans still remember. He made a very good, capable team of Tula guys. Under his initiative, TOZ was renamed Arsenal in 1984; he believed that Tula should have a team with a euphonious name.

In the same 1983, Tula hosted a Spartakiad youth football tournament between Soviet republics, and I, a schoolboy, asked the chief judge of the competition, Vladimir Ivanovich Zuev, to take me as an assistant: to keep statistics and fill out tables. A year later, Arsenal took me on a trip to Tambov and Saransk for the first time as a correspondent. I stayed with the team in a hotel. I forgot my passport – I was already 16 years old – and I was checked in under the name of Anatoly Pesennikov, a young player who did not go with us at that time.

The players were 25 years old, but they seemed so mature and serious to me, and the coach Zolotukhin was a warehouse of wisdom. He told a lot of everyday stories, and the players themselves learned a lot from him. For example, he played chess with the goalkeeper Valery Kleymenov in the evenings, telling him: "Don't go on the streets in the evening, let's play a game or two of chess instead." He told me how after the war he met in Paris with the Grand Duke Felix Yusupov, one of the organizers of the plot against Grigory Rasputin. This person could be listened to for a very long time.

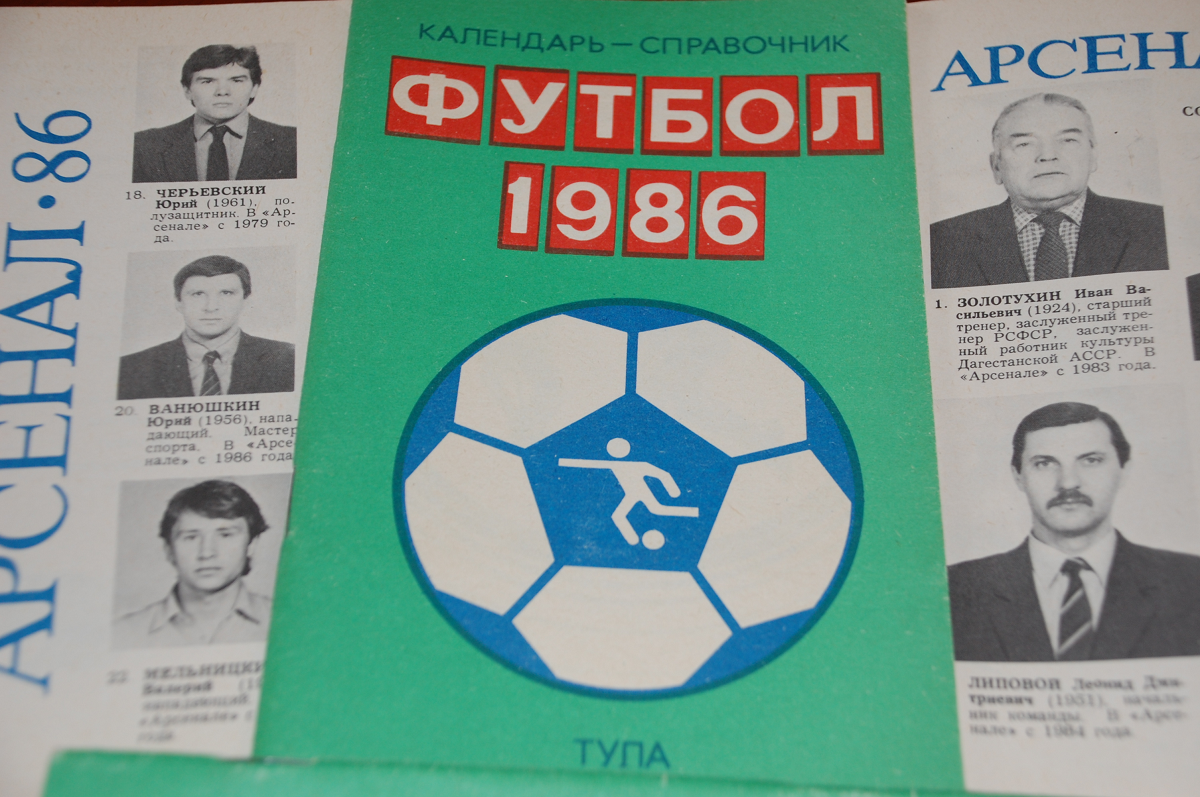

My childhood friend, now journalist and writer, Seryozha Gusev and I had a dream to release a year book. The last one had been published in Tula in 1974, and we wanted to show our journalistic skills and collect statistics in this way. In 1984, on the wave of enthusiasm from the fact that Arsenal took third place in the Second League, we rented typewriters, paid for the services of stenographer because we could not type quickly ourselves, went to Novomoskovsk to interview Vladimir Belousov, our countryman and Soviet champion with Zorya. We even found a participant in pre-revolutionary matches in Tula Nikolai Warmirov, and came up with some headings. We gathered a lot of material, before going to the organization of trade unions. We thought they would help us to publish a book, but in the end the officials did not help. It was very disappointing, because we spent a lot of effort and energy.

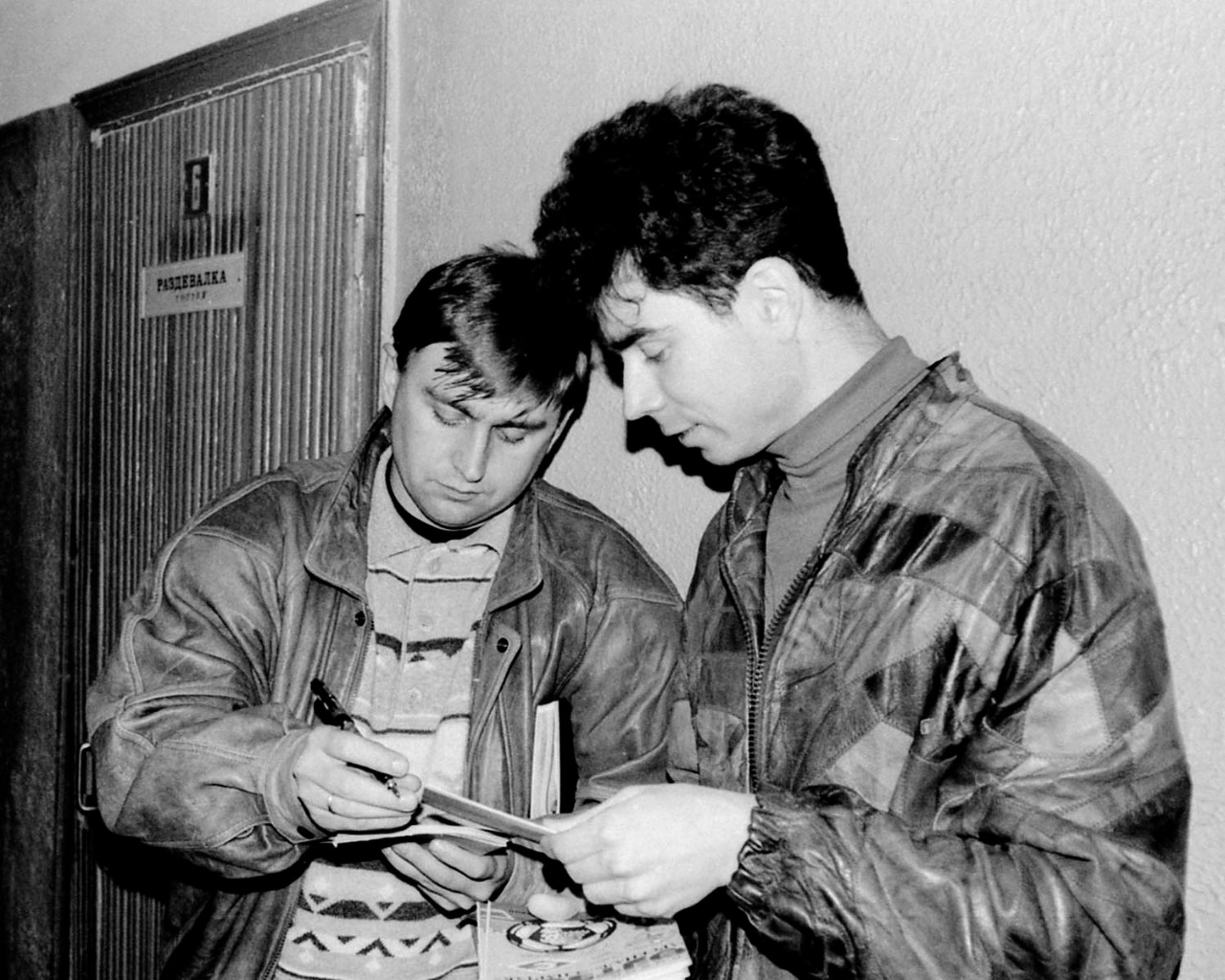

That year book remained in the form of typewritten pages, and in 1986 we still managed to release a brochure. It was a noticeably smaller volume, but through bare enthusiasm and love for football, we published a circulation of 10 thousand copies. Seryozha and I didn't get a penny, but we were still happy that we managed to do it. Then I left to join the army, and my dad bought me a few copies as a keepsake – there's even one with the team's autographs. This pamphlet is dear to me – it is our first work, completely unselfish.

"With the radio operator, we received three rubles for the match and divided the fee in half"

At the age of 16, I asked to be a stadium announcer. We had this role performed by a radio operator: his name was also Evgeny, he was a good and kind person, but I understood that I could announce the composition and other information better. I was easily met, I was confident in my abilities, only the radio operator asked me to divide the fee in half. We received three rubles per match and divided it fairly: one and a half to each of us. For a schoolboy, this was normal money, I saved up for a photo magnifier and printed photos at home.

When I went to Moscow for Higher League matches, I especially liked the voice of Valentin Valentinov at the Luzhniki. I listened to him the way they probably listened to Levitan during the war. I also wanted to repeat his intonation, the approach, as far as our microphone, which was produced by the Tula plant Oktava, still allowed. Even Yuri Gagarin used their microphones in space. Probably, no matter how hard I tried to imitate Valentinov, it was only partly because of the technical capabilities, but I will be honest: I tried.

I also prepared phrases in various languages. When the Brazilians played for Arsenal in the First League in the late 1990s, for example, I would announce in Portuguese: "Andradina scored", "what a beautiful goal scored by Andradina". At first I discussed it with the translator, then I asked Andradina himself and he liked it, saying he felt at home. I spoke in Montenegrin when Djordjevic scored against FC Rostov, but then I was told that it is better to announce in Russian.

There was a case in 1989 when I was almost late for a match. I ran under the stands and saw that the officials were already leaving the referee's room. I told them: "Dear referees, I am the stadium announcer. Please give me the team sheet, otherwise I won't be able to announce the squads, we won't start the match." They gave me the team sheet, of which there was only a single copy. If it had gone missing, it would have been a big embarrassment. I rewrote it for myself and, of course, returned it to the officials at half-time.

The main advantage of this work is that you can say something encouraging. My eldest son Artem and I went to Euro 2012 in Poland. In Wroclaw, before the Russia vs Czech Republic match, it was raining, and the host came under an umbrella to the edge of the pitch and spoke into the microphone directly from there, facing the stands. It seemed like the right thing to do, and I wanted to do it, too.

I decided that another good idea would be to welcome each stand. For example, the 'intelligent' west stand - there sits a calm audience. The 'Mighty' east stand is a community of fans, very creative and energetic people, with drums. I also welcome the 'hot fans' from the north stand, and in the south are the away fans. The stands applaud, and they are pleased.

"I could have worked as a teacher, but immediately after university I went to the editorial office"

I graduated from the Faculty of Russian Language and Literature at the Pedagogical Institute in 1991 and could have become a teacher. I had an internship at school, and always liked to talk to children, to develop them: you feel interested. In the USSR, there was a mandatory distribution after graduation, and I was assigned to the Kamensky district of the Tula region, the most remote one. But when the Soviet Union collapsed, the distributions had no power, so after university I immediately went to work in the editorial office. I was known because I wrote constantly.

I worked in the regional newspaper Kommunar and The Young Communard. At the same time, I made video programs about football, and wrote for Sport-Express and Soviet Sport newspapers. I worked for a fee, a pittance, but to see my name in such solid newspapers was prestigious. Moreover, I wrote not only about football. Arsenal basketball team played at a high level, Tulitsa volleyball team played in the elite division, while from 1997 to the mid-noughties, for example, the Russian Athletics Championships and the Znamensky Brothers Memorial were held in Tula. I remember an interview with Yuri Borzakovsky came out with the title "A star without stardust". When such a famous person is very easy to communicate with, you become his personal fan.

There were a lot of memories with the coaches of Arsenal and their rivals. Vladimir Alyokhin's Arsenal players were his pupils and children of other ages from sports schools in Tula and the region, and Gennady Sarychev worked in Afghanistan in the 1980s: it is clear that there is a different level of football, but he managed to organize the national championship alone.

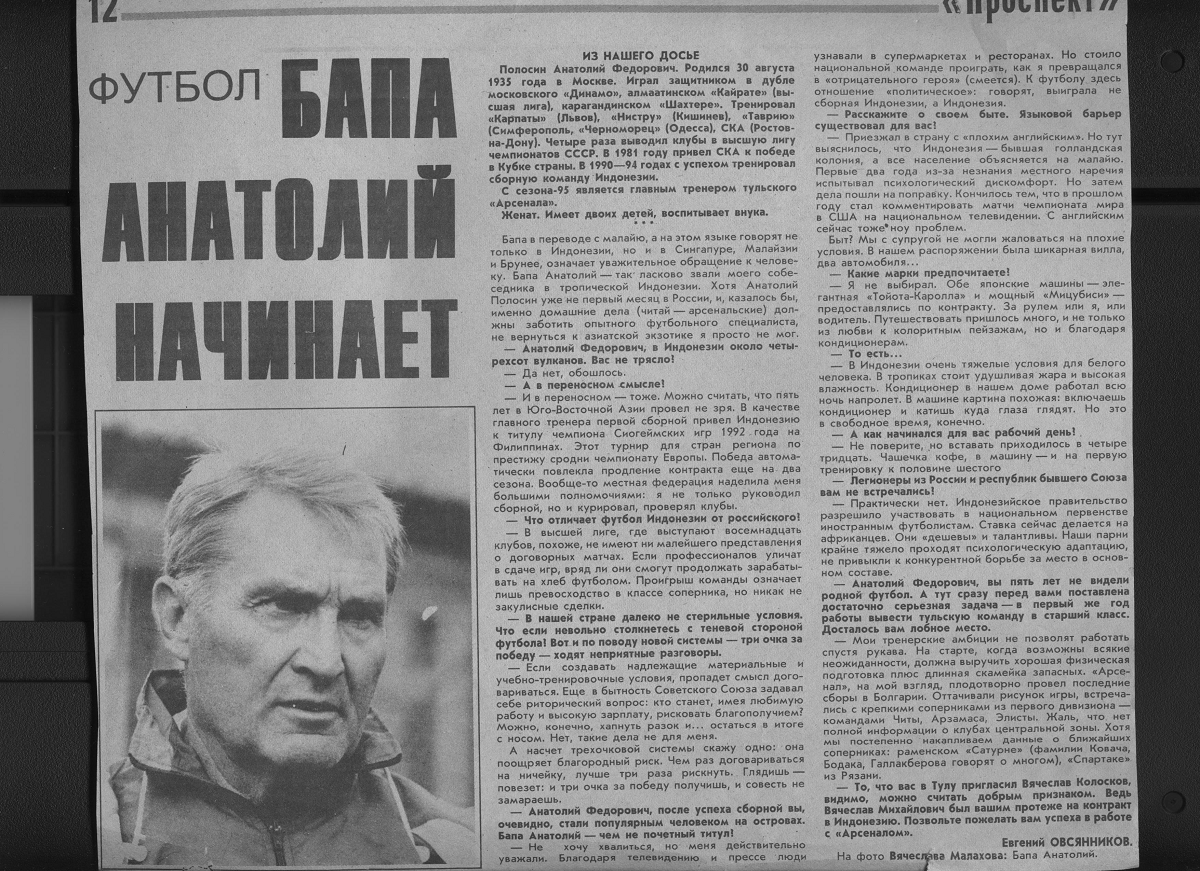

Beniaminas Zelkevicius, who guided Zalgiris in the 1980s, is a collector of paintings and loves impressionists. Anatoly Polosin told a lot of interesting things about how he worked for several years in the tropics in Indonesia. He was idolized there after winning the Southeast Asian Games with the Indonesian national team, but I think he also undermined his health there with this wild heat. Evgeny Kucherevsky spearheaded an era for Tula: he led Arsenal to the First League, and with him they also strove to enter the top division, but the collapse of the ruble in August 1998 intervened. I remember that he had wanted to become a pilot, had it not been for football.

"I did business with my brother: I carried silver jewelry, video equipment"

It was impossible to live on one correspondent's salary. I was engaged in journalism for the soul: I wrote, filmed programs, and conducted broadcasts on the radio, but in order to have something in my pocket, I was also engaged in business. I had many friends in Poland, and I brought silver jewelry from there. Then I switched to video equipment. I ran a business together with my brother Nikolai: we started in 1993, and a few months later I bought an apartment in Tula, then a car.

However, after the default, Kolya left for America. Now his family lives in Cincinnati and supports our Arsenal team from there. My brother works for a social service and helps elderly people. His two daughters work as nurses. In general, my brother is talented: he has a very beautiful baritone, and he sang here in the Philharmonic and in the church choir.

Like many people, it was hard for me, because everything was in chaos. People were broke and left without work, and there was no confidence in the future. But I met love, it saved me. I met my future wife at a football game back in August 1996. Maria was a translator from Germany and helped a Swiss company that was laying the pitch at the stadium. We met at the match between Arsenal and Energia Tchaikovsky. Masha came with a groundsman to see how the pitch would withstand the first match. We saw a rainbow over the stadium and thought it was a sign. My wife had not previously been interested in football, but now we are all family supporters of two Arsenals, from Tula and London, especially our eldest son Artem, who is currently studying in Germany. The younger Denis is involved in football at the club academy.

Then there were the hardest 2000s. Gazprom supported Arsenal [the main sponsor of the club was Tsentrgaz, a subsidiary of Gazprom - Premierliga.ru], and when Viktor Sokolovsky [CEO of Tsentrgaz and president of Arsenal from 1989 to 2004, now Honorary president of the club - Premierliga.ru] went to work on the Federation Council, Arsenal basketball, which was playing at that time in the Super League, collapsed immediately. The football side left the First League, spent two seasons in the second division and went to the amateur levels. The fans even held a symbolic funeral for Arsenal and walked around the city.

It is hard to remember this, because the apotheosis of the fall was training on the ice of the city pond in winter. When there was no opportunity to train with the pitches not ready, several training sessions were held in the city center. We have the beautiful Belousovsky Park: football players and coaches like to walk there, and somewhere there is a photo of a fisherman catching something through a hole, and not far away a football player running. But then we were reborn from amateurs and went through the leagues one after another.

"I decided to write a book about Arsenal in memory of my father"

In 2010, I started writing a book about the club: "The Story of the Real Arsenal". The idea came when my family went on holiday to Egypt. It was a hot night out there, I couldn't sleep and my mind was busy. And I thought: I also have something to tell people about Arsenal, to write something that they will be interested in reading. I could pick up interesting illustrations, present them in the first person, and create an immediate effect. Not only that, but as it seemed to me I fully owned the material having remembered well what I saw with my own eyes, and went through.

I decided to take up the book and dedicated it to my father. He had been hit by a car at a pedestrian crossing, and it was very stressful for me. I then broke my leg at a football tournament and lay in a cast amidst the wild heat, with the whole area covered with smog – there was plenty of time. While I was working on the book, Arsenal revived themselves and started playing in the Second League. It was an amazing time: the whole of Tula was seething with football, we didn't stop at all.

I published the book in 2013 at my own expense after borrowing some from friends, because the entire amount was not enough – I had to find about a million rubles. A long-time friend and a good photojournalist, Andrey Lyzhenkov, helped with the layout. I had no doubt that the book would turn out to be of high quality, so it was very pleasant to read reviews. People ordered the book, for example, from Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and also from St. Petersburg.

I have achieved my goal, although the circulation of five thousand copies has not yet been fully realized. This is quite a lot, and I did not have the leverage to sell in stores, because there is a weak book network in Tula. As a result, I distributed it through various channels: some stores accepted it, they also sold it at the stadium, while I gave it to some personally as gifts, and others ordered it by mail. If Igor Rabiner were in my place, he would probably be able to say that he managed to sell at a profit. I, on the other hand, just recouped the costs.

"Everything was made easy by the joy of the fact that there was football in Tula again"

Arsenal offered me a job in 2012, when I was a sports news anchor on the TVC-Tula TV channel, now the First Tula TV channel. One of the initiators was the general director of the club Maksim Tsarev. I agreed without hesitation, because it was great to be closer to the team that had been reborn, and to help it with your experience and desire. What Arsenal achieved in the following years could only be imagined in the wildest imaginations.

When I started working as a press officer, I realized that I needed to do more interesting materials, interviews, and reports. But I still had administrative work that I was not familiar with before, such as inviting fellow journalists to open training sessions and press conferences. However, everything was done easily, because there was a huge desire and enthusiasm for the fact that there is football in Tula again, that people were coming to the stadium, and we also added joy to the results.

Plus, it is interesting to engage in social activity. Like any other club, we have made friends with orphanages and boarding schools. We are well received everywhere, and the players themselves are inspired by the children. For example, we have been friends with a Russian-language school in Antalya for four years. Previously, at the training camp, students came to us for matches, and we held master classes with them. This school even has an Arsenal corner with our paraphernalia and my book.

At first, I worked in the press service alone. I wrote and photographed. Then the media team grew with the club. The head of club television, Ivan Alifanov, came as an amateur student and started making small stories in 2012, when Arsenal were still playing in the Second League. Maksim Kotenev's photos were noted by venerable colleagues. Aleksey Chestnov is the head of the Media Relations department, but we don't have much differentiation in our work. I have more journalistic, editorial work - pre-match magazines, club website etc - whereas Aleksey is more concerned with social networks and organizational issues.

We have a professional and trusting relationship with the Arsenal management, and we can always build a dialogue. I am always in touch with the general Director Dmitry Balashov, and Alejsey is in contact with the president Guram Adzhoev on all issues. That's how the four of us manage – me, Alejsey, Ivan and Maksim. In some clubs, the composition of the press service is larger, but there are also different budgets.

"We try to be open and sociable, closeness is not modern"

The most frequent requests from journalists are interviews with players. For example, Evgeny Lutsenko played very well last season, scored a lot and was in demand with the press. He was known before, then received a call-up to the national team for the first time in Tula, but, as luck would have it, he got injured. Daniil Lesovoy also proved himself as an interesting dribbler. We had an interview with him with the headline "I dream of playing in the Russian national team". The dream has become a reality for him, and he is progressing so quickly. I can only wish him good luck at Dynamo and with the national team.

There was increased interest when Maksim Belyaev was called up to the national team, and when Artem Dzyuba restarted his career with us on loan. During the pandemic, there was a great demand for the team's chief physician, Alexander Rezepov, because he is an experienced specialist. Previously, Dmitry Alenichev had been very in demand with journalists – for him working in Tula was his first coaching experience – and he showed himself so well.

We always welcome such communication. We are not a secret enterprise, we are a club that represents the city and the region at the highest level in Russian football, trying to give people a holiday and a beautiful spectacle. Being closed is untimely and wrong. We try to be open and sociable. At the same time, players know that you cannot give interviews without the consent of the press service, and in social networks you need to comply with a certain code. If a player gives an interview without warning us, we conduct an explanatory conversation.

Football players, as a rule, have something to tell. I always thank journalists for their work when they send materials, because you can see that the person was preparing for the interview and tried to make the text interesting. Of course, we coordinate the materials, and we suggest that the players read the text in advance.

The main thing is that there are no ambiguities, or moments that discredit the honour of the club by carrying a negative tone. There should be no politics, or things that are not directly related to football and can be regarded as a provocation. I'm not saying that every interview needs to be filtered and slicked down. Football players have the right to express their opinion if they see any shortcomings in our social structure as a civil right, but in general, football should bring joy.

"We understand that when Zenit, Spartak and CSKA arrive, everything will be intense."

I don't always attend the team's training sessions, especially now, in the context of a pandemic. I come only if I need to talk to a player or coach. I used to go to away games with the team all the time, but now because of the coronavirus only sometimes.

One of the memorable trips was to Perm in April 2015. The photographer and I went to the embankment of the Kama River, where there was a sign reading: "Happiness is not far off". Suddenly I saw a letter was lying around, made of plywood about the height of a man. I said: "Let's take a photo, we will return, so to speak, the happiness of Perm – maybe tomorrow we will be lucky." I picked up that letter, put it in its place, then took a photo and put it up on Twitter. The next day we won 1-0 against Amkar, even if we were lucky in parts. That's how we returned the happiness of Perm, and also brought our luck to ourselves.

On match days or on the eve of big games, the workload increases, of course. The higher the status of the match, the greater the interest of the press. We understand that when we host Zenit, Spartak and CSKA, everything will be even more intense. Fifteen journalists from Baku came to the Europa League qualification match with Neftchi; it seemed that everyone from Baku who writes about football was there. The press service of Spartak can send a list of 15 people for accreditation: the club's press service, fan communities, and others. We always try to find a compromise with our security team.

With excitement, we were preparing for our debut in the RPL in the summer of 2014. We sold season tickets very well, and we worked in the office even on weekends, because the fans were lining up. We had to play the first four games at home, and designer Andrey Khabarov and I realized that we were going to have sleepless nights, because we had to make four programs in a row.

We were also seriously preparing for our debut in the Europa League. Our stadium was put in order, the territory of the stadium was improved, and journalists from Baku were given Tula gingerbread cakes and books. Vladislav Kadyrov, a former player of Arsenal and the Azerbaijani national team, also came to us. He was pleased that he was not forgotten in Tula. Everything was festive, but we were not happy with the result.

"With Alenichev I helped pensioners to take out a tub"

Alenichev is remembered for the fact that although he achieved a lot in football, he remained simple and uncomplicated in communication. One day in May, we visited a veteran of Tula football, Evgeny Fedorov. He was a man of advanced age who could hardly get up, but he really wanted to meet Alenichev. We came to him, sat by the bed, and talked.

Leaving, we saw on the landing two pensioners who were going to take things to the country house. They simply asked: "Guys, can you help us?" And Alenichev answered: "Come on." Dmitry Ananko was still waiting for us downstairs – we were on our way to Aleksin for an amateur football tournament – and he was probably surprised when he saw such a picture: Alenichev and I carrying out a heavy tub from the entrance.

Miodrag Bozovic is a very cheerful person. I think he was particularly liked for the way he made jokes. He could lighten the situation with a joke, talk to any football player in a kind way, and create the necessary psychological background. Once we played a traditional match in Turkey between teams of the club's managers and the players. They played and played, then Bozovic stopped to catch his breath, bowed his head and said: "Oh, Grigalava is tired!" He has a natural sense of humour, and knows how to be an easy person to communicate with.

"Before the 2018 World Cup, we gave Dzyuba a good word from the whole family and gave him a coin"

Lukasz Tesak, a Slovakia who played here, spoke excellent Russian. He told us that he had learned from songs, listening mainly to Shufutinsky and DDT. Roman Gerus said that he was raising a foster child, and people of great soul are capable of this. He also sparks memories of a very good, open person. Aleksandr Filimonov, despite his age, kept a high level and helped us from the second division, in the FNL, in the RPL. He has a very serious approach which was felt when he led the defenders.

When we won 1-0 in Saransk against Mordovia and secured a place in the RPL the round before the end of the season, Filimonov got on the bus after the game, turned to the guys and asked in a powerful voice: "Who's in the Premier Liga?" And to him everyone shouted the chorus: "We are in the Premier Liga!" three times. Once in an interview, he told me that he had read Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment twice, not at school, but already at an older age. He admitted that he had not really understood the first time, and then reread it to make sense of all the details. I also know that he read the great work of Lev Gumilyov.

In a big interview with Dzyuba, we discussed wars and battles, and he also said that Bozovic would have been a commander in his army. You can imagine how Artem imagined himself as a warrior with a two-handed sword. It seems to me that he could embody the image of the hero in the movie. In general, he is constantly joking and filled with humour. Everything happens spontaneously, depending on how the situation develops. His competitors at that time were Berkhamov and Khagush, they joked about each other, but I think Dzyuba was number one.

In September 2016, Dzyuba came to Tula with Zenit. I took a picture with him before the match, and we lost 5-0. Someone in the club hung this photo in the old office and jokingly signed it, saying that these are not our people, but friends of Dzyuba. When Artem came on loan, I reminded him about the photo, and he answered with a smile: "Yes, I remember." It was very easy to find a common language with him.

Before the World Cup, we gave him a parting word from the whole family. I brought my sons to training especially, and together we presented a commemorative World Cup coin. They said: "Here, Artem, this coin will bring you good luck at the World Cup." And he went to score. Dzyuba was just the most powerful figure in the media at that time.

Another fun guy is Emmanuel Frimpong, but I don't know how important football was to him at all. Once in Ekaterinburg, he went out in a T-shirt with the inscription 'Dench' on the back. As it turned out, this is his brand of clothing. At the time we were afraid that there would be sanctions against us. In an interview, he said that he could have become a gangster if not for football, because he grew up in some criminal area of London, and football saved him from problems with the law. At the end of 2016 we came to Samara for a match against Krylia, and during the pre-match warm-up we were interviewing one of the players, and suddenly Frimpong stood behind the interviewee and began to jump and make horn signals. I posted this picture on Twitter, and it had a lot of reposts, because Frimpong has a lot of followers. In general, it seemed to me that he was not serious, and football for him is just entertainment.

"We want to get into the Europa League again"

For me, working at the club is a reward for the fact that I have worked in football for so many years and am with the team, that I tried to tell interesting stories about Arsenal in the newspapers, on radio and television. Thanks to my work, I have seen literally the whole of Russia, from Kaliningrad to the Far East, and I have communicated with so many interesting people. I get a lot of pleasure from the fact that Arsenal have been playing in the RPL for six years now, and the team here is clearly not the worst.

I am overwhelmed with happiness when we have full houses, especially in good weather, seeing families come and people with merchandise, and visiting fans come asking for tickets. This means that we are not working in vain. It is not very pleasant when there are not so many people in the stands now, and when there is a lot of traffic and excitement, work is like a holiday. This is a great success when work does not just take up your time on weekdays, but also brings moral satisfaction and joy.

Of special matches, I remember when in the FNL 15,000 spectators came to Shinnik, SKA Khabarovsk and Neftekhimik matches. Of course, I will highlight our debut match in the RPL against Zenit. We faced half a team of participants of the recent World Cup in Brazil. We lost 4-0, but everyone understood that for many guys at Arsenal it was a great time. Before that, they were players of the second and first leagues, and now they are in the RPL.

Our victory over Zenit in the Cup in October 2014, when we had been 2-0 down in St. Petersburg, is also memorable. I was sitting in the press box as it was already getting dark, and the Zenit fans lit flashlights on their phones. Everything was very calm as they already had a premonition of Zenit's victory, and then Arsenal did the impossible: Kaleshin and Smirnov made the score 2-2, and Maloyan scored the winning goal in extra time. Then I couldn't hold it in and just jumped up and waved my hands. Some of my colleagues from St. Petersburg even applauded me kindly, because they understood what a joy it was for us to create such a victory.

And we went to that match by train, because there were financial problems. They even called me from the Championat and asked how we were, and I said: "We'll take the train, we'll be fresh as cucumbers, we'll arrive on the day of the match." Readers had funny comments in the spirit of: "What cucumbers they are there."

I would like us to have a new stadium, maybe holding 20,000 fans, because now Tula has the oldest arena in the league, built in 1959. Our Academy is growing, and we opened a stadium there in November. I want to believe that Tula football is firmly on its feet. We want to get into the Europa League again. It took us so long to get there, and it was over so quickly, that we didn't even get the full kick out of it."

Photo: Arsenal Tula, personal archive of Evgeny Ovsyannikov

Российская премьер-лига

Российская премьер-лига

News

News